By now you’ve probably seen the viral avalanche video of Australian Tom Oye’s avalanche in Chocolate Bowl in the Brandywine area south of Whistler on January 11. The video not only received tens of thousands shares and millions of views, but also made news headlines on Australian television. It serves as a stark reminder that avalanches can occur when the danger rating is forecasted at the “Moderate” level.

There’s a lot of questions left unanswered on why this avalanche occurred, so Mountain Skills Academy & Adventures owner and lead guide Eric Dumerac (IFMGA mountain guide, CAA professional member) has weighed in with an analysis on what happened, why it happened and how a similar avalanche hazard can be avoided in the future.

The Facts

- There’s been significant snow available for transport recently (ie able to be carried and deposited by wind)

- With arctic front winds from the north and northwest, many slopes in the Sea to Sky have been affected by reverse wind loading (ie the wind blowing in the opposite direction that it usually does from the south and southwest)

- South aspect wind slabs are currently isolated, not widespread in the Sea to Sky region.

- The Chocolate Bowl avalanche occurred on a south-facing slope near a ridge top

- The Avalanche Canada danger rating for January 11 was Moderate in the alpine, Moderate at treeline and Low below treeline.

The Chocolate Bowl avalanche on January 11. Note the forgiving run out zone. | Photo by David Cote

The Evidence

- The slope that avalanched had evidence of wind loading with wind ripples on the surface of the snow (time marker 0.01)

- Tom’s snowboard didn’t initially penetrate the snow when he began riding, suggesting the slope had a stiff wind slab (time marker 0.02-0.03)

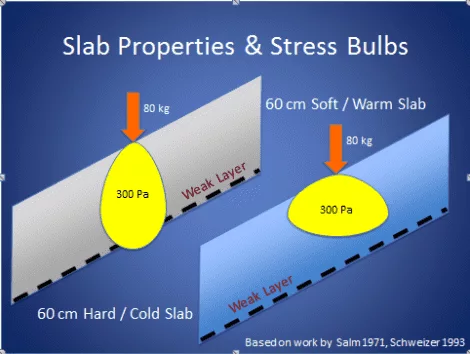

- Once Tom’s snowboard does penetrate the snow, the resulting stress bulb (see figure below) triggers the release of the wind slab and an avalanche ensues (time marker 0.04)

- The wind slab fractures into a jigsaw puzzle of many pieces, a classic example of a very stiff, soft slab avalanche. (time marker 0.05-0.08)

- Near the end of the video, there are plumes of snow coming off the peak in the upper right corner of the screen (time marker 1.22). This suggest winds were still strong at higher elevations when the avalanche occurred

Additional notes from Eric:

“One of the caveats of the Moderate danger rating is that human-triggered avalanches are still possible on specific terrain features. The terrain feature these guys chose to ride was unfortunately one of the specific features susceptible to wind loading in this case. From the video we can see that the snow was still being transported by strong wind, and that means the actual hazard can shift from low-Moderate to high-Moderate or even Considerable before the forecast is updated the next day. Or the forecast might not shift at all, but one must avoid these isolated hazards.”

Mitigating this Sort of Hazard

- Recognize reverse wind loading and which slope aspects are affected. If unsure, use a compass, map or position of the sun to determine the aspect

- Determine if there is indeed a wind slab. Look at the snowfall and wind history the last few days; was there snow available for transport and were the winds strong enough to move it? You can recognize wind slab from having surface clues like ripples and it feels like skiing over a drum-like surface

- Do a quick boot penetration test above the slope you wish to ski. In a safe area (ie above and out of the avalanche start zone) take off your skis/board and walk a few steps in the snow. If your boots suddenly penetrate into the snowpack (ie you feel resistance then suddenly “pop” through), that’s a strong indication there’s a wind slab

- Dig a snow pit and perform a compression test or do a quick hand-shear test. Again, this should be done above and out of the avalanche start zone in a safe, representative and undisturbed plot of snow. For an accurate result, you need to dig at least 20cm below the interface between old snow and new snow

- Avoid steep, ridge top, wind affected or open features, especially convex or unsupported terrain features. Choose lower angle, well supported or treed slopes or choose a lower entrance. This is a good habit for all travel in avalanche terrain.

- Do an indicator run first by skiing lower angle slope to test features and snowpack stability, without the consequence

- Do a ski cut on the slope between two islands of safety in the avalanche start zone. Note: Ski cutting is an advanced technique and should only be performed by experienced skiers/riders. Poorly performed, a skit cut can have disastrous consequences.

Size 1-1.5 avalanche on the south side of Mt. Trorey, Spearhead Range on January 11.

What the Riders in the Avalanche Video Did Well

- The group was out on a clear day with good visibility, when hazards were easier to spot

- The victim had an avalanche airbag, which he deployed immediately. This is especially important for bindings that do not release (like on a snowboard) as the board can act like an anchor, dragging you deeper

- The group chose a slope with a good runout. An avalanche sweeping a victim into trees can cause fatal trauma

- The group had spotters ready to respond to an avalanche scenario

While this video is the most graphic representation of the current wind slab hazards in the Sea to Sky (we’re certainly glad Tom is ok), reports have been coming in of very similar avalanches in the region. Most are occurring on south facing slopes in higher, wind affected areas. Stay up to date on avalanche conditions on the Avalanche Canada website, including field observations from other backcountry users on the Mountain Information Network.

Stay safe out there, and always be on your guard.